OK, I’ll admit it. The title of this post has very little to do with its subject. But I couldn’t resist including a quote from The Princess Bride. Vizzini’s riposte to his giant henchman, Fezzik, is just one of a thousand quotable moments from William Goldman’s script, and if you’ve never seen it you should go rent it now.

Having got that out of the way, the one thing that the title does have to do with the post contents is Greenland. For more than a thousand years, that enormous Arctic island and its indigenous peoples have had an association with Denmark, a country that I visited for the first time a few days ago. The association has not always been a happy one, something that is explored in a great exhibit at the National Museum in Copenhagen. And it was in that exhibit that I came across a fascinating story that lies right at the intersection of the the history of fashion boots and my day job as a museum curator, where I often have to unpack thorny issues of cultural sensitivity.

Peter Jensen is a well respect fashion designer, born in Denmark but now based in London. He studied at the Royal Danish Academy of Design in Copenhagen before moving to Britain to do an MA at the Central Saint Martins College of Art and Design, which he finished in 1999. The fashion press has variously described his clothes as “quirkily humorous” (Vogue), “a breath of fresh air” (WWD), “visually and conceptually captivating” (i-D), and “witty, pretty, proudly individual and imaginative in the extreme” (The Independent). Not at all the sort of the work that might elicit death threats. And yet, in 2009, Jensen found himself in hot water because of a pair of boots.

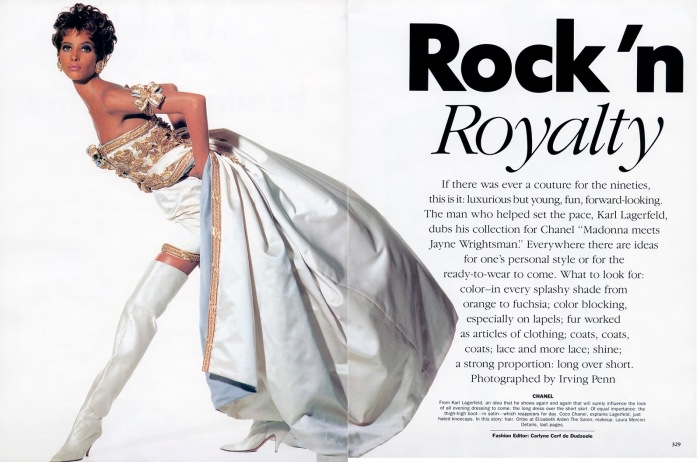

Or, to be more precise, several pairs of boots that formed part of his Fall 2009 Ready to Wear collection. Jensen intended the collection to pay homage to his Aunt Jytte, who, he stated, “owned a chip shop and cab company in the capital of Nuuk, Greenland, and liked fashion in the seventies.” He dedicated the collection to her “because the Danish government paid for me to go to Greenland and the Faeroe Islands to research.” On the catwalk, this played out in traditional cross-stitch patterns, beaded capes, blanket plaids layered with padded jackets, woolly double-bobble hats, and white miniskirts (the latter much beloved of Aunt Jytte in her youth). But one of the most striking aspects of the show were models’ boots: white, leather and thigh-high, with a flowery band around the top.

The boots were inspired by the kamik, a thigh-high boot of reindeer (caribou) skin or sealskin that forms part of the traditional costume of the indigenous population of Greenland. The kamik is one of a wider group of boots that are also known as mukluks. They are worn by Arctic aboriginal peoples such as the Inuit, Iñupiat, and Yupik; they are lightweight, flexible, and – critically – breathable. Air exchange is an advantage in extremely cold conditions, where perspiration may become a factor in frostbite. Mukluks are so effective that today the design is widely used for the industrial manufacture of cold-weather boots.

In the blog of the Penn Museum, Elizabeth Peng writes that “kamiks are imbued with cultural significance: the construction and decoration communicate the maker’s lineage, abilities, gender, chosen activity, and even regional relationships.” Peng quotes Ulayok Kaviok, an Inuit elder from Nunatsiavut, Canada who describes the making of a pair of kamiks as a moment of generational transfer. “During the skin boot production process, elders pass on oral traditions to young seamstresses who are interested in traditional rituals and sharing systems. The first pair of skin boots sewn by a young sibling is a symbol of her bond with the traditional lifestyle and the importance of sharing Inuit and Inuvialuit culture.”

When you realize how much meaning is imbued in a pair of kamiks, it’s perhaps understandable that there were some people in Greenland who were deeply upset by Jensen’s slimline, high-heeled boot designs. As reported in the Guardian, 40 women took to the streets of Nuuk in an official protest against the designer. If that doesn’t seem like many people, consider that the entire population of Greenland is only around 56,000. Scale that up to the size of the USA population, and you’d be talking about a couple of hundred thousand people. So for Greenlanders it was a big deal.

In a press statement, the protesters announced that their short term goal was “to stop these fake kamiks from coming out on the retail market… The Greenlandic people who are opposed to these fake kamiks will not stop until justice has been completed. Anyone can see that Peter Jensen’s kamiks are directly copied from the Greenlandic women’s national costume kamiks, which in Greenlandic is called “KAMISAT”… This is a violation of our collective rights. We have the legal authority to pursue this case, and we intend to do so! … If we imagine a businessman coming up with a product made from rapeseed oil in the original wrapper for LURPAK butter… Isn’t it a blasphemy of a Danish national product? (…) In protest against the theft of others’ culture!”

Jensen was horrified by the reaction, which even included a death threat. “I am shocked that our loving tribute to Kamik boots and beadwork capes could be construed as in any way exploitative,” he said in a statement. “We hoped to bring the world’s attention to the beauty of the Greenlandic national costume. We hoped that the people of Greenland would embrace the attention their heritage has received. The collection and the boots were made out of pure love and meant as a celebration. That I am now getting death threats is really taking this thing out of proportion.”

There’s a curious irony to this story. As I’ve discussed in my book, one of the most fascinating aspect of women’s fashion boots is that they take a traditionally masculine form of dress, imbued with a certain type of power, and co-opt that power to their own ends. People in 1963 were a little shocked by Saint Laurent’s thighboots for women, and the growing popularity of boots during the sixties was part of a wider cultural phenomenon whereby women began to emerge from the shadow of male dominance to make their own way in the world. Cooption was part and parcel of liberation. But for the indigenous people of Greenland, Jensen’s actions looked very much like cultural appropriation. The fact that he was Danish by birth meant that some people saw the dynamic as being that of the oppressor taking from the oppressed.

But perhaps things are not so clear-cut. In a thoughtful piece for the Visit Greenland website, the Greenlandic artist Jørgen Chemnitz argued that the protests against the boot and the wider indignation at its creation were “clear examples of the reactionary forces that prevail amongst those to whom traditions are static and should be handed down as they are without being allowed to develop.” Chemnitz went on to argue that “the Greenlandic national costume is actually an imaginatively put together amalgam of new and old materials from all corners of the globe: sealskin, pearls, silks.”

Image Sources:

- Top – composite catwalk images of Peter Jensen’s 2009 Ready to Wear collection; Vogue.com

- Bottom – West Greenlandic women in traditional costume featuring kamiks; Greenland Today

Selected References:

- Chemnitz, Jørgen. “Deconstructing the Greenlandic National Costume.” Visit Greenland. Retrieved June 11, 2019

- Holmes, Rachel. “Designer Death Threats.” The Guardian, online edition, March 26, 2009. Retrieved June 11, 2019

- Peng, Elizabeth. “Fashion, Fur, Flowers, and Flannel.” Penn Museum Blog, May 12, 2015. Retrieved June 11, 2019