I’ve been reading “Out of Town: A Life Relived on Television” (1987), which is an autobiographical memoir written by Jack Hargreaves (1911-1994). Hargreaves is a fascinating character, who would be worth a blog post in his own right (if I had another blog that was not fashion-oriented). Although he was a successful businessman, broadcasting pioneer, and more than at home in sophisticated London society, most people in Britain remember him as the white-bearded host of Out of Town (1963-1981), a gently-paced show that explored life in the English countryside. In my childhood memories, the post-Sunday lunch TV spot is inextricably linked with images of Hargreaves driving his horse and trap along a country lane to the strains of Recuerdos de la Alhambra.

Hargreaves saw significant changes over his lifetime, as did anyone of my parent’s generation, something that is very clear when you read his reminiscences of growing up in the years after the First World War. In the countryside, technology had seemingly triumphed over a way of life that had remained largely unchanged for the previous two hundred years or more, a process that was accelerated in the aftermath of the Second World War. The nineteen fifties and sixties, with their space rockets and brave talk of a New Elizabethan age, seemed to represent the culmination of all this, and the triumphalism of the space age and what Harold Wilson called “the White Heat of Technology,” was reflected in the fashions of the time… Courréges, YSL, and especially Pierre Cardin.

This was the time when the fashion boot came of age; the radical step of co-opting a previously masculine form of dress as a fashion item for women reflected a new (if still largely unrealized) role for women in the society of the future. New materials born in the laboratory rather than the fields allowed for sleek, colorful variants of the boot at prices that made fashion egalitarian in a way that it had not previously been.

This was the time when the fashion boot came of age; the radical step of co-opting a previously masculine form of dress as a fashion item for women reflected a new (if still largely unrealized) role for women in the society of the future. New materials born in the laboratory rather than the fields allowed for sleek, colorful variants of the boot at prices that made fashion egalitarian in a way that it had not previously been.

But the end of the sixties saw the beginnings of a revolt against this technocentric paradigm. The future didn’t seem quite as bright and idyllic as we had been promised. The war in Vietnam dragged on, sparking violent political protests. Crime rates soared, and the recreational drugs that had promised to open new doors of perception became, instead, a plague that blighted urban areas and the lives of those that lived there. People began to look at the past, through rose-tinted spectacles (sometimes literally), as a lost Golden age. Forgetting the reactionary politics, wars, and imperialism of the time, they sought out fashions that recalled those days.

We’ve looked at some of these in earlier posts, and it’s a topic that gets a whole chapter to itself in the new MFW book (note the shameless plug). This began in the last years of the nineteen sixties as a fascination with the fashions of the Victorian and Edwardian eras; in footwear, this manifested itself in a new category of “granny” boots, that added retro laces or buttons to the knee length boots of the time. By the early seventies, nostalgia had become focused on the 20s and 30s, as typified by the fashions of the London store Biba, and its footwear manifestation was the platform sole. We tend to think Glam Rock when we see boots of this era, but in fact they were a (successful) attempt to fuse the leg-hugging boot of the late sixties with a heel and sole that reflected fashions popular in the Golden age of Hollywood, four decades earlier. But these were, for the most part, youthful fashions; for the older generation that had consumed the early “youthquake” fashions of the sixties first-hand, the nostalgia for past times had evolved into something rather different.

We’ve looked at some of these in earlier posts, and it’s a topic that gets a whole chapter to itself in the new MFW book (note the shameless plug). This began in the last years of the nineteen sixties as a fascination with the fashions of the Victorian and Edwardian eras; in footwear, this manifested itself in a new category of “granny” boots, that added retro laces or buttons to the knee length boots of the time. By the early seventies, nostalgia had become focused on the 20s and 30s, as typified by the fashions of the London store Biba, and its footwear manifestation was the platform sole. We tend to think Glam Rock when we see boots of this era, but in fact they were a (successful) attempt to fuse the leg-hugging boot of the late sixties with a heel and sole that reflected fashions popular in the Golden age of Hollywood, four decades earlier. But these were, for the most part, youthful fashions; for the older generation that had consumed the early “youthquake” fashions of the sixties first-hand, the nostalgia for past times had evolved into something rather different.

One of the most popular British sitcoms of the mid-70s was The Good Life (1975-1977), the story of Tom and Barbara Good (played by Richard Briers and Felicity Kendall), a suburban couple who abandon the rat race of modern life in favor of “self sufficiency,” converting their suburban home and garden into a smallholding, much to the horror of their upwardly mobile neighbors, the Leadbetters. Few people actually went this far, but there was a great enthusiasm for natural materials around the home – quarry tiled floors, rattan chairs, stripped pine furniture, earthenware plates and mugs, hand-woven rugs, etc. Terrance Conran’s “Habitat” chain did booming business.

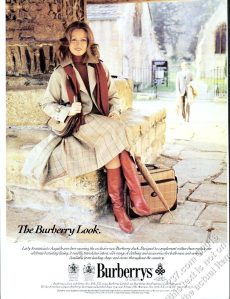

In the world of fashion, this manifested itself in what Vogue called “the new ease” – natural fabrics like wool and cotton, worn loosely in “sloppy-joe” sweaters and full skirts that hit the leg just below the knee. It was a countrified look, heavy on tweeds, plaid, capes, and expensive raincoats by the likes of Burberry and Acquascutum that harked back to the glory days of the country house set and weekend house parties.

In the world of fashion, this manifested itself in what Vogue called “the new ease” – natural fabrics like wool and cotton, worn loosely in “sloppy-joe” sweaters and full skirts that hit the leg just below the knee. It was a countrified look, heavy on tweeds, plaid, capes, and expensive raincoats by the likes of Burberry and Acquascutum that harked back to the glory days of the country house set and weekend house parties.

The new style of dress came with its own distinctive fashion boot. In contrast to the tight, vinyl styles of the late sixties, this was made of high-quality leather or suede, stack heeled, and loose fitting, with a tendency to settle in extravagant folds around the ankle. It was this feature that gave the boots their quite unflattering nickname – “baggy boots,” but the loose fit gave added balance to a silhouette that, combined with the fuller skirts, placed the weight low on the body. Because the hem of the skirts just covered the tops of the boots, they also provided much-needed leg coverage in cold or wet weather.

This neo-country style was massively popular in Europe and, to a certain extent, North America during the second half of the nineteen seventies. To my mind, it was absolutely embodied by the series of press advertisements for Burberry shot by the Queen’s cousin, Patrick Lichfield. These featured the ultra blue-blooded model Lady Annunziata Asquith, daughter of the 2nd Earl of Oxford and Asquith and great granddaughter of British Prime Minister H.H. Asquith, wandering round the estates of various stately homes in a Burberry trenchcoat, expensive woolens, and boots. It was a look enthusiastically embraced by the mail order catalogs of the time, which failed to see there was something slightly unrealistic about a woman donning expensive, heeled boots to plow through muddy fields with the family spaniel.

in a Burberry trenchcoat, expensive woolens, and boots. It was a look enthusiastically embraced by the mail order catalogs of the time, which failed to see there was something slightly unrealistic about a woman donning expensive, heeled boots to plow through muddy fields with the family spaniel.

In reality, the country fashions of the nineteen seventies were rather like Jack Hargreaves himself; for all their outward aspirations of rustic simplicity, they were actually products of a thoroughly urbanized society. When The Good Life finished, in 1977, its breakout star, Penelope Keith (who played the spectacularly snobbish Margot Leadbetter) went on to play a widowed member of the country gentry, Audrey fforbes-Hamilton, in To the Manor Born (1979-1981), swapping her suburban kaftans and polyester jumpsuits for tweed skirts, sweaters, and pearl necklaces. It was the absolute apotheosis of the neo-country look. But when she went outside, in the fields, she wore Wellies.

Image Sources

- Rustic fashions: Janet Frazer catalogue, Autumn/Winter 1975

- Fashions by Pierre Cardin, 1968: via Tumblr

- Granny boots: via Pinterest

- Baggy Boots: Janet Frazer catalogue, Autumn/Winter 1975

- Lady Annunziata Asquith, shot by Patrick Litchfield for Burberry: via Ebay

Selected References

- Anon 1974. Fashion: Fall Guidelines: The New Ease in Fashion. Vogue, Jul 1, 1974: pp. 40-65.

- Griggs, Barbara. 1974. For the Girl Who Likes a Little Loose Living. The Daily Mail, Aug 19, 1974. Pg. 10.

- Hargreaves, Jack. 1987. Out of Town: A Life Relived on Television. Dovecote Press

- Nemy, Enid. 1974. Boots have changed – especially in price: droopy look. New York Times, Sept 20, 1974: pg. 47.

SaveSave

At the time, those “extravagant folds at the ankle” were given the also unflattering named “crushed.” The phrase “extravagant folds” really captures their effect, though: sumptuous.